What is it about old letters that come to light later that is so appealing to our imagination? In our age of instant communication via email and social media, letter-writing is a rare practice. Why write someone a letter when you can Skype them instead? But for people a century ago, no other means of staying in contact existed. A letter was a personal thing, even if it took some time for it to arrive or for a reply to come back.

For historians and novelists they are precious gifts. They contain details of people’s daily lives, which they probably thought banal and of interest only to the writer and the recipient. They reveal aspects of the writer’s personality and emotions. Sometimes, they are a valuable commentary on contemporary events, telling it how it was – or at least how that person perceived them.

World War I and letter-writing

World War I created a great wave of letter-writing, assisted by improvements in literacy during the latter part of the 19th century. Soldiers at the Front wrote letters home during the mind-numbingly boring periods of inactivity between offensives. Many have been lost to posterity, but countless examples have survived, and they paint a rich picture of life in the trenches, the pendulum swings of morale and the daily preoccupations of the troops.

I used the epistolary format in a short story entitled ‘Bertie’s Buttons’, in which a young soldier relates to his parents the unofficial truce of Christmas 1914. It was common for opposing sides to swap mementos during these brief meetings, including buttons – hence the title of my story, which is published in my collection, French Collection: Twelve Short Stories.

Equally valuable are the letters from the people at home to their loved ones at the Front. A few years ago, we visited a hamlet in Southwest France, where I live. One of the residents had discovered by chance in his attic a letter from his grandmother, Palmyre, to his grandfather, who was fighting in the trenches. Palmyre had been left with several children and a farm to run when her husband went off to war. She had not seen him for nine months.

Palmyre tells him about the crops and what she has done with particular fields. She also says how much she misses him: “We were so happy together.” It was unusual at that time for people to express their emotions in writing. Fortunately, there was a happy ending: he came home, and they had another three children.

I can feel another story coming on!

Hidden love letters

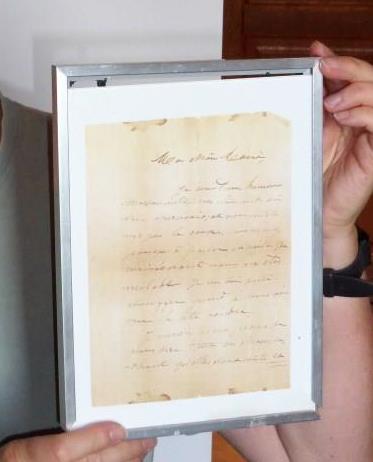

For me, best of all were the letters we saw in a guest house on the Mediterranean island of Corsica. The owners had found them in a blocked-up niche in the attic when they restored the house. It turned out that the village school master had written them in the 1890s to the daughter of the house, Marie. Her parents would have strongly disapproved of their liaison, considering him to be beneath her socially. The lovers corresponded via a secret letter drop, and it appears that their relationship was a stormy one!

The star-crossed lovers were never destined to be together. She had to yield to an arranged marriage to a distant relative, common on Corsica at that time, to keep the family lands together.

Why were the letters hidden? What happened to the school master? What was life like for a young woman on Corsica at that time? These questions kept circulating in my head, so I took this true story and wove it into my first novel, The House at Zaronza, which follows the fortunes of Maria (I slightly altered her real name) and ranges from 1900 to World War I and beyond.

The House at Zaronza was first published in 2014, but I published a second edition with a new cover and editorial amendments in 2018. To mark its second birthday, I am making it free on Amazon Kindle for a few days. You can also read it for free in Kindle Unlimited.

“Beautifully written, evocative of this small island. A lovely book.” – Tripfiction

“Emotionally powerful…Vanessa Couchman writes with intelligence and skill.” – Historical Novels Review

Copyright © Vanessa Couchman 2020. All rights reserved.

Reblogged this on Vanessa Couchman and commented:

On the Ocelot Press blog this week, I look at the material and inspiration that letters written many years ago provide for historians and novelists. And The House at Zaronza, based on a true story of hidden letters that came to light more than a century later, is free on Amazon Kindle for a few days.

LikeLike

Sometimes ancient letters are the only things that can tell us what life was like. Some of the letters unearthed at Vindolanda Roman Fort reveal aspects of daily life in late 1st century Roman Britain that could only have been imagined till they were through the conservation processes. I just happen to be writing about Vindolanda just now but haven’t yet sneaked the ‘letters’ into my writing in progress….now how to do that? I wonder. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

The letters from Vindolanda must be fascinating and a precious record of daily life. I’m sure they would add an additional perspective to your work in progress.

LikeLike

A really interesting post, Vanessa. I can highly recommend your short story collection and ‘Bertie’s Buttons’ was one of my favourites. As you know, I was fortunate to discover an amazing cache of old letters in my late mother’s wardrobe which were written to my grandmother by her friend Ethel North. Ethel was lady’s maid to Lady Winifred Burghclere, the sister of the 5th Earl of Carnarvon who, along with Howard Carter, discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb. I am currently putting all the letters into book form so that other people can read them as they are a fascinating account of life during the Inter War Years and also portray an extraordinary friendship that develops between an aristocratic mistress and her servant. There is more information at https://ladyburghclereandethel.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Melissa. Good luck with your own book.

LikeLike